The Quad 2.0 is being hailed by some, but many are also calling it an extension of the United States of America’s Hub-and-Spoke model. Critics have questioned the relevance of Quad 2.0 as there is no template or blueprint, and the inclusion of the new members in the Quad 2.0 is based on no specific parameter and criterion. Keeping all this in mind, the present article would revisit the brief history of the Hub and Spokes model with respect to the US, as well its alliance members, and also discuss how the Quad is inevitably coming across as the new extension of the Hub-and Spokes model.

San Francisco System- ‘Hub and Spoke model’

On 6th September 1951, a conference of 49 allies agreed to meet in San Francisco to secure the Japanese Peace Treaty and aimed to codify the regional security arrangements. Along with this, the US aimed for more direct ties with Japan, and it resulted in a bilateral alliance under the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security, which made Japan dependent on the US militarily, diplomatically and economically. It also focused on the benefits that Japan would receive by being a part of the US, like the security guarantee and free western world markets. The resources of Japan became a major part of the American Cold War Strategy with the region and the greatest advantage for America was the strategic hold of a military base in Northeast Asia.[1] All in all, Japan emerged as a key player within the US Grand Strategy, it laid a strategic cornerstone for the future and worked towards the containment of Communism. It also helped deter the aggression caused by the Soviet. Japan emerged as the catalyst for the developing regional strength as it helped the bigger goal of the US made network for regional security as well as economic advantage, which grew as the centrepiece for greater U.S. interest and cooperation in the Asia-Pacific region. Therefore, all of this resulted in the informal setup of the ‘Hub-and-Spokes Model’, with five key bilateral alliances which become essential for the U.S. foreign policy in the post-war period as well as the Cold War period. Since Japan was an important element of its regional strategy, in anticipation of the upcoming San Francisco conference, America sought the support from the select regional allies who were earlier distrustful of Japan, as they had been subjected to colonial as well as war atrocities and had become extremely weary of the re-emergence of Japan as a major regional power and player.[2] It is also important to understand that in the backdrop of July 1951, a Trilateral Security Treaty between Australia, New Zealand and the United States of America (ANZUS) had been formalised and also aimed to serve to protect the wary allies due to Japan’s past history. ANZUS was critical in the formation of the alliance along with working towards the regional growth, and it also paved the way for a Mutual Defence Treaty which materialised between the U.S and the Philippines in August 1951.[3]

The larger understanding of all this was the growth of the US centred regional balance of power. A position in each of these countries offered strategic positioning of the US military forces, accessibility to natural resources and focus the vast populations towards the West which would collectively reduce the communist influence, power and would hedge the offshore expansion of the Communism. So, the US decided to use the SFS as well as Japan to increase its regional security, growth, and influence. Thereby, the system aimed for sufficient economic opportunity for Japan which would serve the greater goal of growth in the Pacific region.[4] In October 1953, a mutually advantageous negotiation of additional bilateral security agreement was formed with South Korea after the conclusion of the Korean War and the Formosa Resolution of 1954 with Nationalist China (Taiwan), and acted together to secure the US and the supported states. In 1954, the US Hub-and-Spoke model finally included Thailand through the Manila Pact, also known as the Southeast Asia Collective Defence Treaty in September 1954. Together, all of these treaties were extremely essential for the American Foreign Policy, as it led to an increase in the US hegemony. As the Cold War progressed, it led to the establishment of a multilateral set up paving the way for Southeast Asia Treaty Organisation (SEATO), which was a by-product of the Manila Pact, the ANZUS and the Asia-Pacific Council (ASPAC), but all fell short of initial expectations. Later in August 1967, the dominant voice of the Asian determinism led to the beginning of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) which was formed with Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Singapore. It aimed towards the purpose of regional cooperation in sectors of economy, social, cultural, technical, educational and other fields, and together this grouping marched towards the promotion of regional peace and stability, abiding rules of respect for justice, the rule of law and adherence to the principles of the United Nations Charter.[5] Thereby, the San Francisco System, also known as the Hub-and-Spokes Model which emerged as a network of bilateral alliance pursued by America in the region of East Asia, made the US as the ‘Hub’ and countries like Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Australia as ‘Spokes’. This system of Hub-and-Spokes aimed at commitments of military, economic and political between the US and its Pacific Allies looking towards dominant security architecture in the region of East Asia. The US through this system could exercise its control over the smaller allies, which is active in the present times as well in the absence of multilateral security architecture like NATO. The aftermath of the Korean War made the US more engaged in this region. In the present situation too, the San Francisco System is essential, as apart from military protection, economic access of trade and aid, it also helps fend off Chinese aggressiveness in the region of East Asia. [6]

The Hub-and-Spokes Model could well be a little compared to the Wallerstein’s World Systems Theory based on the ‘core and periphery concept’, as the Core or the Hub is the US and the Spokes or Periphery were the smaller countries, though the bases of both of them are different. In the Hub and Spokes model, the smaller countries benefited widely by giving control over its space to the US, but the World Systems theory was more of an economic system, making countries like Venezuela, Banana Republic as they only and exported bananas only for the use of the US and were completely dependent on the Americans. Both highlight the US dominance and how this US dominance and leadership is true for the present Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD) formation, which again makes the US a central power with smaller powers aimed to yet again contain a Communist power, China. Therefore, it can be said that the QUAD is a return of the Hub-and-Spokes Model.

Quad 1.0

The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue or the Quad began as a grouping with the United States of America, Japan, India and Australia. It was called the Tsunami Core Group as it was an ad-hoc grouping which dealt with the devastating earthquake and tsunami in the Indian Ocean in December 2004[7], and paved the way for a new kind of diplomacy. This was done by swiftly mobilising the tsunami aid and coordinated towards a multilateral humanitarian assistance and disaster relief operation, and the template was formed based on issues of regional concern and mutual cooperation. This grouping gained prominence when the Arc of Freedom and Prosperity in 2006 was formed, and this Arc envisioned a network of states across the Eurasian continent to expand the diplomatic efforts of Japan and aimed to promote the freedom and the rule of law.[8] Taro Aso, the Foreign Minister of Japan had commented that significant attention was given to the democratic, free-market nature of the future of Quad, and was vastly expanded as a network to countries like Viet Nam and Ukraine. In December 2006, the geographical bounds began to fall into to place and in the Joint Statement between India and Japan, it was said that both the countries were eager to begin the dialogue along with like-minded countries in the region of Asia-Pacific to address mutual interest.[9]

In May 2007, the first meeting of the initial Quad took place at the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) in Manila and this meeting aimed at being an informal grouping with common interests focused on being dialogue partners and looking at disaster management issues. In September 2007, the first Quad US-India Malabar series began, and it had four navies along with that of the Singapore Navy. This exercise took place in the Bay of Bengal, focussing on exchanges of personnel, drills in sea control and multi-carrier operations. China increased its campaign against this grouping, thus making the US, India and Australia reluctant to formalise this grouping. Many other critics questioned the lack of purpose and objectives, and some also called it the Asian NATO.[10] During this time, the newly elected Kevin Rudd Government in late 2007 also decided that the Quad wasn’t watching their outlook, and announced that they wouldn’t be participating in the Quad Dialogue which was supposed to be held in January 2008. This crumbled the Quad 1.0, and Australia didn’t even participate in the Malabar exercises. From 2007 to 2017, there were several intra-Quad dialogues of the ministerial level and the evolution of traditionally bilateral exercises into mini-lateral arrangements illustrated the growing alignment of the Quad nations in the time between Quad 1.0 and 2.0.[11]

Quad 2.0

In the later 2017, the revival of Quad 1.0 was done and paved a way for Quad 2.0. Quad 2.0 was as controversial as Quad 1.0. The critics again said that there was no blueprint or template, and many believed that China couldn’t be contained. Some also called it an improbable platform for cooperation in the area of defence. ASEAN as a regional player saw the Quad surpassing its centrality. In November 2017, Japanese Defence Minister Taro Kano gave an interview that again focused attention on the Quad idea, and this time, Quad 2.0 had gained support from Australia. This was because in the 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper, Canberra confirmed its strong commitment to trilateral dialogues with the countries like the US, Japan and India, and was open to working with its Indo-Pacific partners in the other pluralistic arrangements. The Asia Reassurance Initiative Act depicts America’s full commitment to Quad 2.0, and it also covers the security dialogue between the four countries to address the security challenges in the region of the Indo-Pacific. It promotes a rule-based order, respect for international law, a free and open Indo-Pacific and a dialogue intended to augment.[12] From this it is clear that Quad 2.0 has its focus in the region of the Indo-Pacific, and it is supported as Japan has its Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP), India has its Indo-Pacific Region Policy (IPR), the US also has its Free and Open Indo-Pacific Policy (FOIP). In 2017, Canberra also agreed to partner with its Indo-Pacific partners, which makes it clear that the Quad 2.0 has Indo-Pacific focussed. Also, ASEAN adopting the Indo-Pacific Policy has also given a clear indicator that the future of mutual cooperation is in the region of the Indo-Pacific with special emphasis on Maritime cooperation and building military capabilities within the maritime domain. The Quad and the ASEAN nations can also work together towards cooperation, and aim for multilateral security arrangements in the region. This has led to an ASEAN-led regional security architecture through their status as dialogue partners, and are also members of the ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting-Plus, the East Asia Summit, and the ASEAN Regional Forum and also attend the US-led Rim of the Pacific biennial naval exercise.[13]

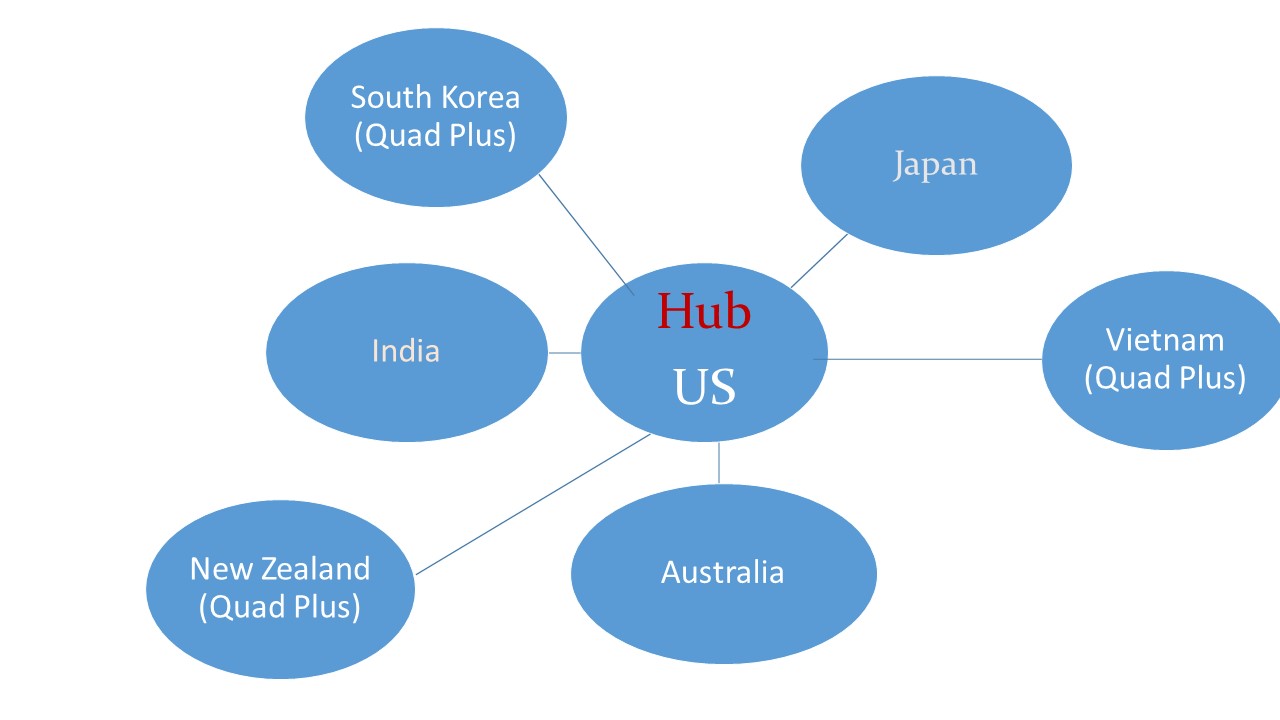

Quad 2.0 comes in with the idea of Quad plus countries, with the plus countries being Viet Nam, South Korea and New Zealand. The question remains that the Quad 1.0 was questioned for no definitive blueprint and this question again gets carried forward to the Quad 2.0 as what is the criterion for the inclusion of Viet Nam, South Korea and New Zealand? Is there any blueprint or template for bringing these countries in as the Quad plus countries? It is important to understand that the Quad was made to deal with China’s rise to a global power, as almost all these countries, whether Quad or Quad plus have some or the other issue with China, and on the contrary each of them have an excellent economic relationship with China. The Quad is not only about economic relations but also about security relations and all Quad countries enjoy liberal democracies and the partners also enjoy liberal political freedoms.[14]

It is important to understand as to why Viet Nam, South Korea and New Zealand have been chosen. Viet Nam is one of the strongest ASEAN nations, with one of strongest standing army along with the strategically placed natural harbour Cam Ranh Bay. Viet Nam has been having several issues with China in the South China Sea, and as Viet Nam has been coming closer to the US, their relations have also improved. Also, Viet Nam has been the ASEAN Chair this year and has also been selected as a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council to serve during the term of 2020-2021. South Korea is already in an alliance with the US, making it a previously associated ‘Spokes’ country, the same going for New Zealand. South Korea still has some security issues and has been actively involved in balancing relations between the US and China, but New Zealand has no strategic perspective and still it has been accepted as a Quad plus country. The US clearly says that it is looking for partners who would mutually cooperate and coordinate with them, so Japan, India and Australia are putting in more efforts and can be called as ‘middle powers of the Quad’. Viet Nam, South Korea and New Zealand are already Quad plus countries, but can be fitted into the realm of Spokes. Hence, the Quad 2.0 can be termed as the return of the Hub-and-Spokes model.

(The views expressed are personal)

[1] Steven Kent Vogel. 2002. “U.S.-Japan Relations in a Changing World” published by Brookings Institution Press, Washington, D.C. pp.1.

[2] U.S. Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States. 1951. “Asia and the Pacific” (in two

parts) Volume VI, Part 1, Edited by Fredrick Aandahl, U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 35

URL: http://digital.library.wisc.edu/1711.dl/FRUS.FRUS1951v06p1 (Accessed 26 June 2020)

[3] Please refer to the U.S. Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States. 1951. “Asia and the Pacific”, pp.45.

[4] U.S. Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States. 1951. “Asia and the Pacific”, pp. 34.

[5] Kim Beazley. 2003. "Whither the San Francisco Alliance System?" published by Australian Journal of International Affairs Vol. 57, No. 2, pp.326.URL: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10357710301741?journalCode=caji20

(Accessed 27 June 2020)

[6] Kent Calder. 2004. “Securing Security through Prosperity: the San Francisco System in Comparative Perspective” published in the The Pacific Review, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 135–157.

[7] Tanvi Madan. 2017. “The Rise, Fall, and Rebirth of the Quad” published by War On The Rocks dated November 16, 2017. URL: https://warontherocks.com/2017/11/rise-fall-rebirth-quad/

(Accessed on 27 June 2020)

[8] Taro Aso. 2006. “Speech by Mr. Taro Aso, Minister for Foreign Affairs on the Occasion of

the Japan Institute of International Affairs Seminar: Arc of Freedom and Prosperity:

Japan’s Expanding Diplomatic Horizons” (speech, Japan Ministry of Foreign Affairs,

November 30, 2006). URL: https://www.mofa.go.jp/announce/fm/aso/speech0611.html

(Accessed on 27 June 2020)

[9] Ibid.

[10] Brahma Chellaney. 2007. “‘Quad Initiative’: an inharmonious concert of

democracies” published by Japan Times dated July 19, 2007. URL: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/

opinion/2007/07/19/commentary/quad-initiative-an-inharmoniousconcert-of-democracies/#.Xgz8p-LQg6g(Accessed on 27 June 2020)

[11] Indrani Bagchi. 2008. “Australia to Pull Out of ‘Quad’ that Excludes China,” published by Times of India dated February 5, 2008. URL: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/Australia-to-pull-out-of-quad-that-excludes-China/articleshow/2760109.cms

(Accessed on 27 June 2020)

[12] Huong Le Thu. 2019 “Introduction-Quad 2.0: New perspectives for the revived concept Views from The Strategist Insights” published by Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) dated 13th February 2019.URL: https://s3-ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/adaspi/201902/SI134%20Quad%202.0%20New%20perspectives_0.pdf?Ml2ECFvmUJTTFzK.RsBIsskCRRAqEmfP (Accessed on 27 June 2020)

[13] Bhubhindar Singh. 2018. “The Quad as an enabler of regional security cooperation” from The Strategist Insights” published by Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) dated 13th November 2018 .URL: https://s3-apsoutheast2.amazonaws.com/adaspi/201902/SI134%20Quad%202.0%20New%20perspectives_0.pdf?Ml2ECFvmUJTTFzK.RsBIsskCRRAqEmfP(Accessed on 27 June 2020)

[14] Walter Lohman.2019. “What is Quad 2.0? The fundamentals of the Quad Quad 2.0: New perspectives for the revived concept Views from The Strategist Insights” published by Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) dated 13th February 2019.URL: https://s3-ap-southeast2.amazonaws.com/adaspi/201902/SI134%20Quad%202.0%20New%20perspectives_0.pdf?Ml2ECFvmUJTTFzK.RsBIsskCRRAqEmfP(Accessed on 27 June 2020)