In recent years, a new wave of flare up in Sino-Japanese geostrategic competition in the Pacific has galvanised the region by adding traditional and new players into the equation. The once neglected region in the post-Cold War world order, is becoming the microcosm of power-politic between regional and extra regional powers. In other words, the region is regaining its lost stature and becoming a hotbed of great power rivalry. So far, all powers, both emerging and established, have used their soft power through provision of much-needed foreign aid to advance their national interests in the region.

Enjoying an exceptionally high maritime importance amongst others, Japan initiated its formal engagement with the region in the post-World War I period when it had global ambitions. During the Second World War, however, Japan occupied Micronesian states while it fought in parts of Melanesian countries. Occupying the region, argue analysts, would have put Japan in a strong and competitive position. After the war and its quick impressive economic growth, Japan started pouring modest amounts of foreign aid to the region to make compensations for the damage it caused during the war.

By contrast, China established its diplomatic relations with the Pacific Island countries in 1970s, an era that had ushered in two historic phenomena. Firstly, the wind of decolonisation, though later than the rest of the world, was sweeping through the region. The two colonial powers of the time, France and Great Britain, were giving self-determination rights to the island nations. They were becoming new members of the United Nations (UN).

Secondly, the UN Seat was given to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) from the Republic of China (Taiwan) after it failed to gather enough international support for its cause. It also coincided with the breakaway of China from its communist ally the Soviet Union. Thus, the US encouraged more cooperation with China than with Taiwan. This marked the beginning of Sino-Taiwan aid competition for diplomatic recognition. Ever since, China has expanded its presence in the Pacific providing foreign aid with an aim to deny Taiwan diplomatic space internationally.

This Chinese unprecedented and multi-layered expansion in the region has alerted Japan, which does not wish to see China in its backwaters. Although both Japan and China have set up their own development frameworks to lead the way in their cooperation with the region, Japan has been praised for being effective in delivering development projects and being transparent in provision of concessional loans. By contrast, China has been blamed for predatory infrastructure investments and soft loans with unfavourable terms and conditions.

Furthermore, to deepen and broaden cooperation with the island nations, Japan spearheaded the first South Pacific Forum summit in 1997. This forum was renamed as the Pacific Islands Leaders Meeting (PALM) in 2000 and institutionalised as a “triennial event” to be held in Japan thereafter. In an assertive and brazen manner, Beijing established the China-Pacific Islands Countries Economic Development and Cooperation Forum in 2006 and presided over the first summit meeting in Fiji. Since then, PRC has held summits in China in 2013 and Samoa in 2019.

This begs the question as how the two economic giants would benefit from their aid competition in the Pacific region. There are multitude of justifications for the two donors to win over the micro-states. Japan’s ambition to secure the permanent seat at the UN Security Council is at the heart of Sino-Japan aid competition in the region. The eight South Pacific Forum member countries that enjoy UN membership are critically important for Japan’s bid to get Security Council permanent membership. It is with this grand objective that successive Japanese governments have been vying for support from the island nations. Surprisingly, the Pacific leaders at PALM 8 in 2018 expressed “support for Japan’s bid for permanent membership” of the UN Security Council.

From Beijing’s strategic considerations, a democratic and influential Japan as a permanent member of the UN Security Council will endanger China’s global interests. Thus, understanding the seriousness of the matter, Beijing is fervently using the full force of its economic and diplomatic might to derail Japan’s futuristic ambitions. PRC has therefore furnished the island nations with foreign aid, foreign direct investment and tourism to lure them not to support Japan’s bid at the UNSC. Instead China is pioneering the UN Security Council reforms to give “priority to increasing the representation of the developing countries and granting greater opportunity to more small and medium-sized countries to participate in the Security Council decision making.”

Appearing in the midst of aid competition amongst a plethora of donors, the Pacific island states are playing their political and diplomatic cards carefully and wisely by playing one economic giant against the other in order to secure more concessional loans, funding for development projects, foreign direct investments, tourism, and support for climate change. For example, in the first three PALM summits the island leaders expressed their concern about the lack of financial commitments from Japan.

Taking stock of the dissatisfaction, Beijing in the first China-Pacific Islands Countries Economic Development and Cooperation Forum that was held in Fiji in 2006, pledged US$373 million in concessional loans to the island countries. However, since 2011 China has provided soft loans and gifts to its diplomatic allies in the Pacific worth over US$1 billion, which is only an estimate by different sources because China does not make the actual amount public.

Instigated by the sense of rivalry, Japan also made financial pledges in various sectors worth US$383 million. However, at the eighth PALM summit in 2018 a number of new initiatives were introduced where Tokyo will not publicise its aid budget to the Pacific region anymore. Instead, it will diversify the scope of its engagement in the region by focusing more on areas such as disaster risk reduction, climate change, maritime security, and measures to combat illegal fishing.

China’s growing influence and expansion in the Pacific has precipitated the efforts of traditional and regional donors to engage more broadly with the island nations. For instance, Australia initiated its Pacific Step-up policy while New Zealand adopted its Reset policy. All of these policies are geared towards curtailing China’s expansion and encouraging the island states to reduce their development and financial cooperation with Beijing. Despite facing with multi-pronged bulwarks erected by its regional rivals, China has made remarkable inroads in pressing ahead with its expansionist agendas.

So far neither of the regional and traditional powers have been able to limit China’s activities in the region. Ten of the fourteen island states have diplomatic relations with China and have deepened and broadened their cooperation significantly over the past many years. Despite being criticised for predatory infrastructure investments and aiming to open military bases in the region by indebting the island nations, Pacific states have not reduced their engagement with China. It has only expanded to the dismay of China-hostile powers.

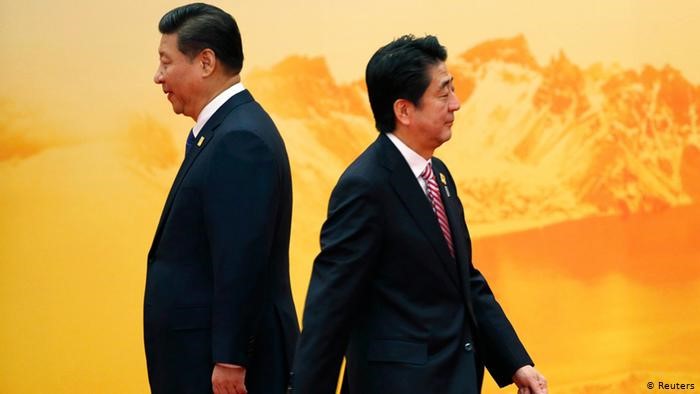

Picture Courtesy-Reuters

(Saber Salem is Doctoral Research Fellow with the Jindal School of International Affairs, OP Jindal Global University. His areas of interests are Pacific region, climate change, climate migration and foreign aid diplomacy.)