Why India is interested in Visegrad countries?

Visegrad countries have become important for Indian foreign policy in recent times. The visit of Indian Minister of External Affairs Dr S. Jaishankar to Hungary and Poland in August 2019 sheds light on India’s engagement with central Europe, the region that used to be off the radar of Indian foreign policy over the last 30 years. This paper focuses on four countries in the region: Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia, which form the Visegrad Group (V4). It examines the potential for cooperation in the economic, political and strategic domains to show why the region does matter to India. It suggests that in order to boost cooperation India may engage Visegrad countries in a V4+ mechanism at the soonest.

Visegrad countries, which used to enjoy close and friendly relations with India during the Cold War period, got far less attention from New Delhi following the end of communism and their transformation to free market democracies post-1989. No Indian prime minister (PM) has paid a visit to the region in this new era, and the last time the Indian PM was in Poland, for instance, was as long ago as in 1979. Even the very active Narendra Modi, who has paid numerous visits to Europe, has overlooked the Visegrad countries during his first term in office. Travels of Indian ministers of external affairs to these countries used to be very rare and the sporadic visits of Indian presidents could not repair the impression of neglect by India. In fact, a visit by the current Indian External Affairs Minister Dr S. Jaishankar to Warsaw on 28-29 August 2019, made him the first Indian foreign minister to visit Poland after a 32- year gap.

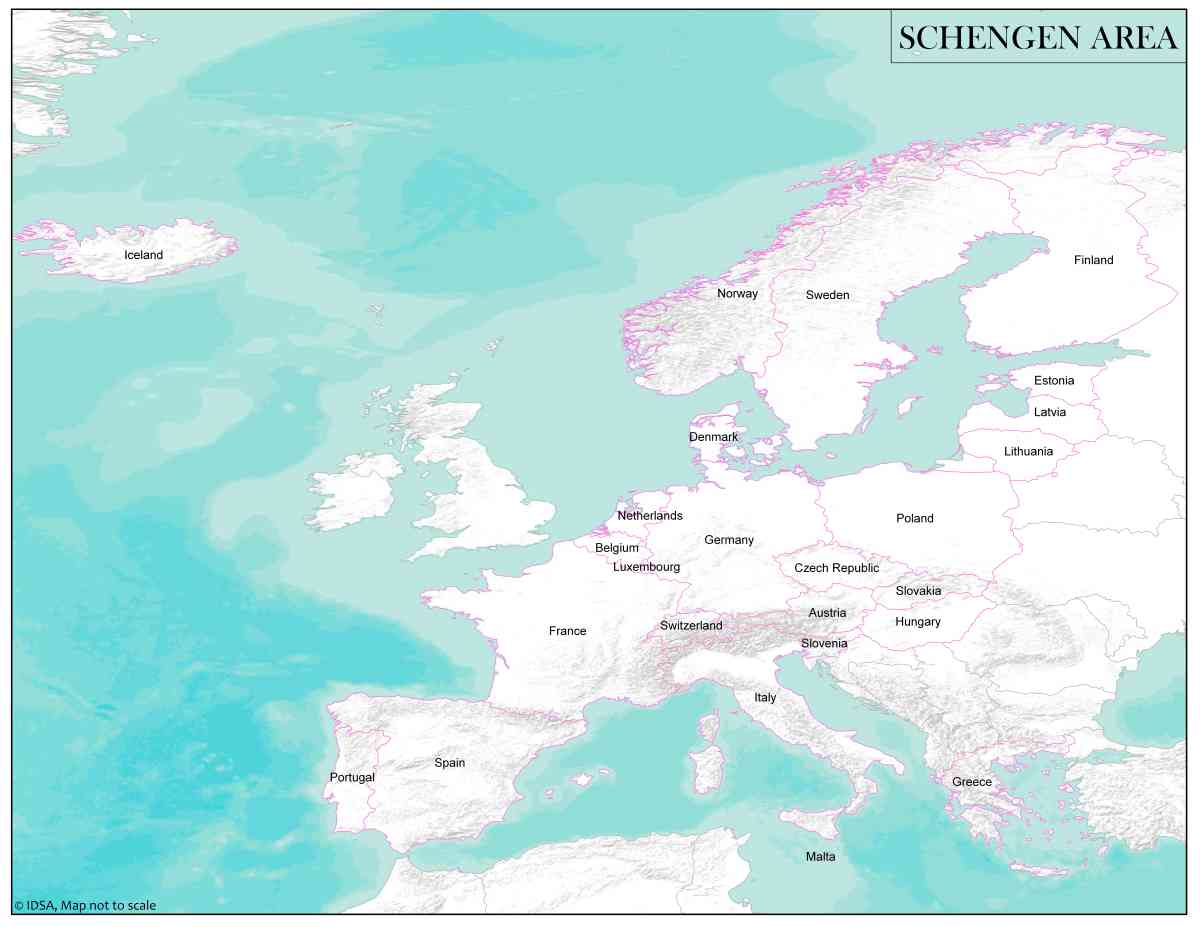

As a result, India might have missed how the region transformed remarkably over the last three decades. The Warsaw that Dr Jaishankar has recently seen is wholly different from what former PM Morarji Desai witnessed 40 years ago. As central European countries redirected their foreign policies from the east to the west, they formed the Visegrad Group in 1991 to support their efforts at joining the European Union (EU) and NATO. After accession to the EU in 2004, the V4 remains one of the most vibrant sub-regional groups in Europe, with growing economic and political clout in the Union. With fast economic development, close historical ties and convergent strategic views with India’s, the time is ripe to explore the potential for closer Indian cooperation with the V4. Two areas highlight the region’s value for India.

Economic Cooperation:

The first is economic cooperation. Four Visegrad countries have been among the fastest growing in the whole European Union over the last decade. They all grew above the EU average (2.0 per cent GDP) in 2018, with Poland recording the third highest growth of GDP (5.1 per cent) among 28 EU members and Hungary coming just behind it (4.9 per cent). Together, the V4 make up the 12th largest economy in the world, worth over US$1 trillion (S$1.39 trillion), which is over one-third of India’s size, and offers a consumer market of 64 million inhabitants, which is 12.5 per cent of the EU’s total. Yet their trade with India - US$4 billion (S$5.56 billion) in 2018 - is far below the potential level. While the V4’s share in the EU’s external exports stood at 10.1 per cent in 2016, its share in the EU’s exports to India was only 3.6 per cent. Similarly, while they count for 9.6 per cent of the total EU imports, in the case of India it was only half of that proportion at 5.6 per cent of EU’s imports from India in 2016. Poland, with an economy of over US$550 billion (S$764 billion) - the biggest in the region and the 6th largest in the EU - is only India’s 49th largest trading partner with the trade of goods worth US$2.4 billion (S$3.3 billion). All that suggests that there is potential to grow the V4-India trade volume.

As these V4 countries, which are heavily dependent on the European market, are searching for new economic partners beyond Europe, India seems to be an attractive destination. With a long tradition of cooperation in Indian industrialization from the 1960s-80s, they offer today new and low-cost technologies in areas required for Indian modernization programs, from infrastructure to sanitation and agro-processing. Not many Indians are aware that companies that are already well-established in India like Bata, Bella India, Home Credit and Skoda are from the V4 region. Also, Indian firms like Infosys and Tata have major investments in the V4. The region has already become a new destination for Indian tourists and a place for the growing Indian diaspora. With one of the lowest unemployment levels across Europe, they may soon become even more amicable to migrants from Asia, as the recent decision by the Czech Republic to grant 500 high-skill long stay visas to Indian professionals, indicate. Hungary, for several years, already offers 200 scholarships to Indian students. With the relaunching of direct flights between Warsaw and Delhi in September 2019, another barrier for closer ties will disappear.

Political Cooperation:

Second is political cooperation. As India’s global ambitions grow, it needs more trusted partners in Europe, to promote its interests in relation to the EU, the US or in multilateral forums, like the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) or the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG). The V4 countries send as many as 106 members to the European Parliament out of 751 in total, hold influential positions in the EU institutions - like Donald Tusk, who was the former Polish PM, has been serving as the President of the European Council since 2014 -and play a strong role in shaping both the EU internal agenda and external policy. To give only two recent examples, in June 2019, three Visegrad countries (without Slovakia) blocked the EU from deciding on an overly ambitious aim of committing to net zero carbon emissions by the EU by 2050 and, in July 2019, they derailed the nomination of Franz Timmermans for President of the European Commission, against the wishes of larger countries like Germany and France. Their harder approach to irregular migration to Europe since the 2015 refugee crisis – closer to the Indian attitudes – has now become a mainstream EU policy on migration. As they make their voices better heard in the EU, they all support a stronger EU cooperation with India, including more pragmatism in negotiating a free trade agreement. By stronger relations with V4 countries, India’s partnership with the EU would be more balanced and pragmatic.

At the international level, the V4 are favourable to award a UNSC permanent seat to India and supported the country’s bid to join the non-proliferation regimes (NSG, Wassenaar Agreement, Australia Group, Missile Technology Control Regime) where all four are members. With shared historical experiences among themselves (no colonial heritage, transition from socialism to market economy post-1989), they find more common ground with India on a number of international challenges from climate change to terrorism than many developed Western countries. For instance, it was during the Polish Presidency of the COP 19 meeting in Warsaw in 2013 where a compromise in global climate change negotiations, including a concept on intended nationally determined contributions, was agreed. Also, at the recent COP 24 in 2018 in Katowice, Poland promoted the idea of ‘just transition’ – a policy to ensure that the shift to green energy does not hurt the workers and communities that rely on outmoded industries.

Security Cooperation:

Visegrad countries are attached to the idea of sovereignty and territorial integrity and share ideological affinity with India. As new beneficiaries of globalization, they oppose protectionism and support free trade. They support India in the fight against international terrorism, including cross-border terrorism. It is also not without significance that the central European group sends one non-permanent member to the UN Security Council. How important this may be, India has witnessed in August 2019, when Poland, chairing the UNSC then as a non-permanent member handled the Kashmir issue in a more than helpful way to India. It not only stood by the position that the problem must be resolved “bilaterally” between Pakistan and India but, as chair, it also refused to raise the issue at the forum on Pakistan’s request and when China brought it for “closed consultation” at the UNSC, no President’s Statement was issued in order not to give it more international recognition.

Finally, the geopolitical situation is also now more favourable for a stronger V4-India cooperation than ever, since the end of the Cold War. The EU has acknowledged the importance of India in both economic and strategic terms and commits to deepening cooperation in many fields, as illustrated in the first ever EU Strategy on India of 2018. The Visegrad countries, having gone through a short period of warming up of relations with China, as the 16+1 format testifies, are now looking for a more balanced approach to Asia where India plays a prominent role. Also, India’s growing stronger defence and strategic cooperation with the US – a crucial security ally of the V4 – is opportune for V4-India cooperation in security, defence and strategic issues. The Czech Republic or Poland, both of which used to be important sources of weaponry to India in the past, are willing to come back and participate in Indian defence modernization.

Regional Approach:

Apart from bilateral cooperation with individual Visegrad countries, India can also explore possibilities of a sub-regional approach to signal its growing engagement with the region. The V4 is already well-experienced and has tested mechanisms in place for cooperation with major non-European partners. In the V4+ formula, they have held summits with leaders of Japan (since 2013), South Korea (since 2015) and Israel (since 2017). The V4+ is also run at a lower level, with ministers of foreign affairs or defence of major non-European countries. These meetings usually allow for an overview of broad areas of cooperation in economic, political and security fields and has led to practical initiatives of cooperation in selected areas.

Besides the V4+, it is important to mention that the Visegrad countries also engage in other multilateral platforms for cooperation with non-EU partners. They launched the 16+1 formula in 2012 for cooperation with China. They also joined a separate mechanism of the Three Seas Initiative (TSI) focused on connectivity and infrastructure development in central Europe, where the US plays a special role. The visit of the US President Donald Trump to the TSI Summit in Warsaw in 2017 was an important signal of American reengagement in this part of Europe.

This openness of the V4 for cooperation in multilateral formats may get a nod from Indian Prime Minister Modi who likes this model of cooperation for both practical (saving time and travels) and political (prestige) reasons. He had invited leaders of SAARC for his swearing-in ceremony in 2014, African leaders for the Africa-India Summit in 2015, ASEAN leaders for Republic Day in 2016, and travelled to Sweden for the NORDIC plus India Summit with five north European countries in April 2018. A meeting with the four central European leaders could be a good opportunity for him to make up for lost time in relations, explore potential for cooperation and to boost stronger bilateral engagement.

The Way Forward;

As V4 countries have already been eager to renew the old friendly ties with India for some time, and the visit of Dr Jaishankar to the region in August 2019 has signalled an opening of a new chapter in the relations. As one can read in a Joint Statement from his meeting with his Polish counterpart, “he conveyed India's readiness to engage more actively in the region of central Europe, which should have a positive impact on the overall EU-India cooperation. He also expressed India’s desire to engage with Poland in the Visegrad format.” A V4+ India cooperation format seems to be a good option for all sides provided one risk is taken care of. If V4 countries have not invited India to this cooperation yet, it was possibly because they did not want the regional format to replace bilateral cooperation but rather to supplement it and bring added value. If this concern is taken care of, then the new road to Europe is ready to travel.

References:

1. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/india-explores-partnership-with-visegrad-group-in-central-europe-with-jaishankar-visit/articleshow/70862243.cms

2. https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/eu-budget/long-term-eu-budget/2014-2020/revenue/own-resources/national-contributions_en

3. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/international-business/prague-opens-up-to-offer-high-skill-long-stay-visas/articleshow/65776129.cms

4. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/jun/20/eu-leaders-to-spar-over-zero-carbon-pledge-for-2050

5. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-48818715

6. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/chinas-unsc-kashmir-plea-in-polands-court/articleshow/70694945.cms?from=mdr

7. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/chinas-unsc-kashmir-plea-in-polands-court/articleshow/70694945.cms?from=mdr

8. https://www.indiatoday.in/world/story/pak-efforts-to-internationalise-kashmir-snubbed-as-unsc-consultations-end-without-outcome-1581759-2019-08-17

10. https://dipp.gov.in/publications/fdi-statistics

Pic Courtsey-

(The views expressed in the article are the personal views of the author.)