Chinese investments in Myanmar’s infrastructure

On 17th February 2021, a coup d’état in Myanmar began on 1st February 2021, when democratically elected members of the country’s ruling party, the National League for Democracy (NLD), were deposed by the Tatmadaw- Myanmar’s Military- which then vested power in a stratocracy. The coup d’état that occurred the day before the Parliament of Myanmar was due to swear in the members elected at the 2020 election, thereby preventing the power transition. The coup has been challenged with nationwide protest and attracted international attention with its violent display of power and blatant disrespect of human rights. Being condemned by the international community jeopardizes the bilateral and multilateral relations Myanmar has formed over the years, case in point Biden Administration’s sanctions on Myanmar. In that context, China- Myanmar relations, which have forged as friendly relations, are under threat and the diplomatic and economic relations are also under suspicion as the military coup is prolonged. With the threat of military coup ruining the China- Myanmar relations, this article will analyze how the China-Myanmar infrastructure relations are currently under threat as the military coup progresses, and how this progression can affect on a long- term basis.

“A coup in no way is in Beijing’s interests, as Beijing was working very well military wise and infrastructurally up at this point”. Yin Sun Co-director of East Asia Program, China Program at the Stimson Center in Washington D.C.

China and Myanmar relations currently stand at a critical point following the military coup in February 2021. The Myanmar coup, which saw the military taking over the power after National League for Democracy (NLD) and Aung San Suu Kyi retained their power in November 2020 general elections.[1] The military coup, in recent memory of Myanmar, stands as the most controversial and forceful measure taken in the mainland. This provides many difficulties if understood from the point of both the nation’s bi-lateral and diplomatic relations. Chinese foreign ministry also stands concerned with the violent display of power, and as the coup prolongs, the friendly relations between both the nations are also in danger, especially if you see the long-term consequences of the One Belt and Road Initiative undertaken by Beijing[2].

The coup has been already condemned a lot by the international community. Biden administration has applied sanctions, India is also trying to diplomatically pressure Myanmar into resolving the situation and the United Nations has termed it as a blatant violation of the human rights mechanism. This situation is not familiar for Myanmar. From the 1980s until 2011, the Southeast Asian Country was under the threat of isolation from the international stage and China was the only country that continued its support for the region[3]. In this context, the Chinese factor plays an important role historically and contemporarily. Even the land of Myanmar provides rich resources like timber, jade, and natural gas and as Myanmar allows China to access the ocean on its southwestern flank, strategically, this relation stands as very crucial. However, the implication of these bilateral relations is not only limited to the strategic sphere, but the infrastructural consequences also, which subsequently formulate the diplomatic ties of the nation are under threat[4]. Despite that fact, Myanmar’s military leaders are on board in terms of a full embracement of Chinese relations, the breakage in relations can cause a de facto loss in sovereignty for the state which can be detrimental seeing the current vulnerable state of the nation with its ongoing crisis at hand. This juncture is quite important for Myanmar, as the western influence is at an all-time low considering the Rohingya cleansing that has taken place in the land and the military coup that is happening on the ground.

De-escalation of tensions is important for Beijing as China has always referred to Myanmar as its “friendly neighbor”.[5] Considering the influence that India, China’s rival in Asia, has maintained in the Asian continent, Myanmar stands critical for Chinese long-standing influence and power dynamics to shape Southeast Asian politics. Myanmar's diplomatic relations with China have been forged by domestic factors rather than international or regional factors. The relations between the nations are denoted as “pauk- phaw”, which means kinsfolk in Burmese[6]. This term first appeared in the 1950s and in no way does this term represent that China- Myanmar relations have always worked in parallel synchronicity. Mutual recognition between both nations started in the 1940s, which led to a decade’s worth of establishment to reach certain warmth in diplomatic relations in the 1950s with border treaties in the 1960s solidifying the relations in Asia[7].

China always had a series of complex domestic politics, as well as erratic relations with the whole international community, provided by a false sense of stability and then exaggerated actions of displaying a strength of its sovereignty. Myanmar provides a crucial geopolitical and geostrategic advantage in the region. Post-Cold war period, Myanmar’s decision to follow a neutral foreign policy and maintaining balance relations with the USA and China was a challenge, especially for Beijing to maintain ties that close. The Battle Act of 1950 put a cap on military assistance from the US side, allowing Myanmar to veer on developing its military strength and ties[8]. “The Burmese Way to Socialism”, adopted in 1975 to curb the ethnic clashes between minorities like Kachina and Chin, and strengthening the Panglong Agreement between the major ethnicities, was adopted to restore stability in the nation[9].

Burma’s official recognition of China in 1950 has established a relation of controversies and trade developments in the area. While Myanmar had issues till 1980 about the working of the communist party in China, and while China was supporting of Communist party of Burma (CPB) until Myanmar’s central government, the organization disbanded in 1989 thereby cutting any political ties with China[10]. After the Tiananmen Square incident in China, and western embargos, Myanmar was the place where Beijing established new economic ties and from the 1990s and early part of the 2000s, Myanmar was the investing ground for China especially in military and infrastructure projects which created the foundation of a long-standing diplomatic tie between both the nations.

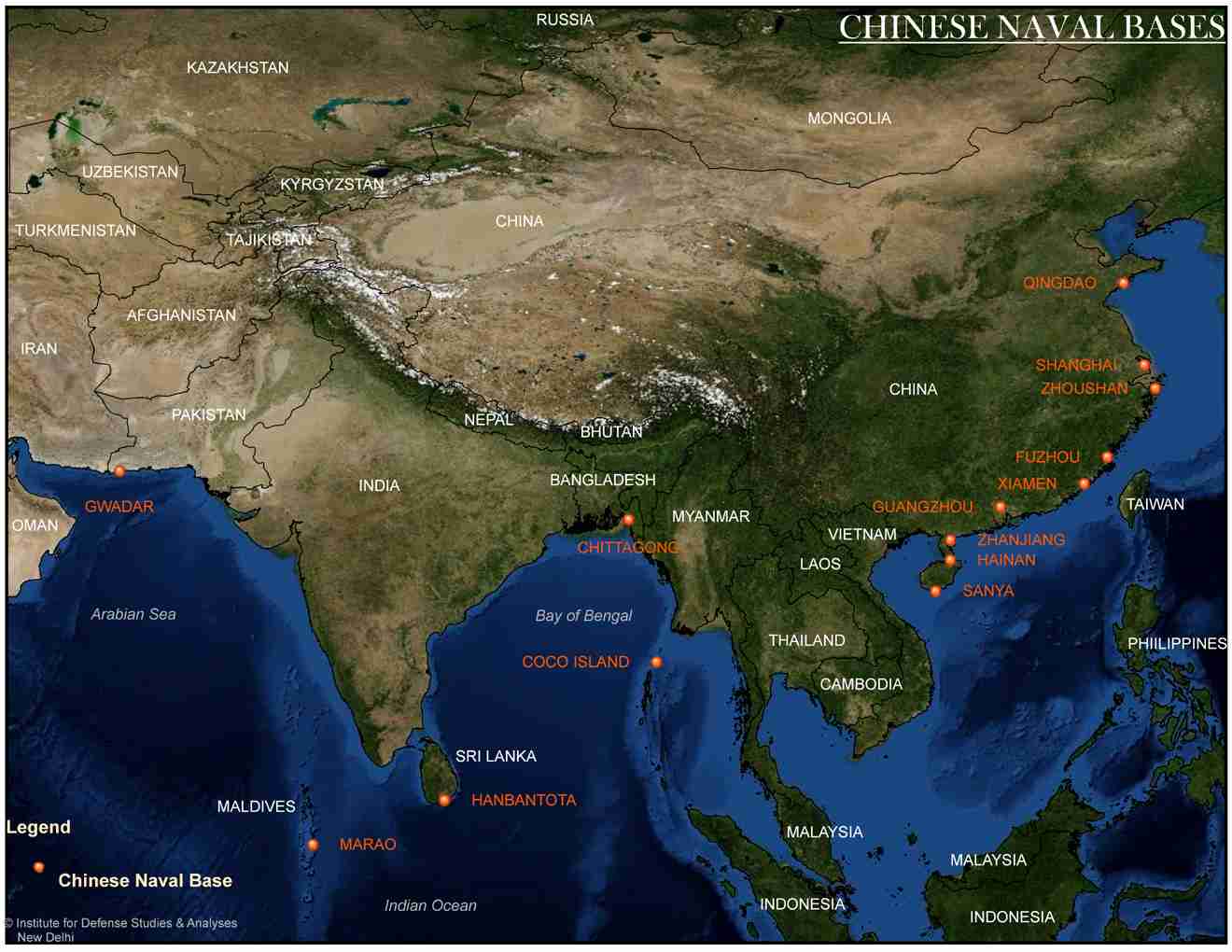

Once the 2000’s democratization efforts of Myanmar aligned with its governmental changes, China’s relations turned more into optimizing its developmental efforts. One of the initial efforts that were the Myitsone Dam Project which had agreed upon in 2009 but was suspended in 2011 but in 2016 under Aung San Suu Kyi, these large- scale Chinese ventures were resumed[11]. China- Myanmar Oil Pipeline was also a simultaneous project which was halted in 2012 but was continued in 2017[12]. This indicates an important pattern between the relations of these two states. Despite historic differences between both nations, Aung San Suu Kyi has been the catalyst that has allowed Chinese projects to take place in the land and keeping politics away from business is difficult. The Chinese tolerated Aung San Suu Kyi but maintained the ties as she enabled the essential infrastructural and economical projects in the region. Myanmar also serves as a gateway to the Indian Ocean and Bay of Bengal for China due to its geostrategic and geopolitical viewpoints that allow these economical ventures[13].

The geostrategy, economic and regional powers have allowed a foreign policy to have surged with these projects and infrastructural developments. With Myanmar’s military tutelage on its domestic and foreign policy and re-calibrating, its changes by coding economic ventures into the long-standing military and strategic ventures, China and Myanmar’s influence in Southeast Asia are worth noting. The most effective of these partnerships was concluded in 2018 when China inducted Myanmar in its One Belt and Road Initiative[14]. When the 15-article memorandum was signed regarding the initiative, China created the option of bypassing the Malacca Strait to gain an alternative exit to the Indian Ocean. Linking Myanmar’s Mandalay, Yangon, and Kyaukpyutahat in the Bay of Bengal to its Yunnan Province which is not even linked to the sea are one of the most successful strategic agreements[15].

The investment of One Belt and Road Initiative projects will allow the China- Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) to be more substantial in its geopolitical fortunes and interests. CMEC medium to long term development and subsequent success will represent how BRI in Southeast Asia will continue to operate under Chinese interests and incentive Chinese policy commitments further into the global paradigm[16]. The ventures will also allow areas like the Yunnan province in southeast China, which continue to be underdeveloped to restore their economic strength. Yunnan province is one of those areas which will serve as a broader perspective for Chinese ventures into the region. As per the Chinese ministers, the Yunnan province provides a major gateway to East Asia and Southeast Asia, which allows it to create and exert its influence[17]. Despite the province standing as a riddled area amongst the drug trafficking routes which are opened out of the Golden Triangle and suffer from cross border violence, stability minded Chinese authorities have demonstrated the methods to curtail this drug trade and trafficking. With the promise of curbing the ethnic armed organizations and eliminating the narcotics trade, it is a Chinese venture to reduce the poverty and issues of trafficking and violence by the end of 2021, which stands as the overarching objective of the CMEC and BRI. Myanmar’s CMEC is very similar in comparison to China as Pakistan’s China- Pakistan Economic Corridor as it will allow a strategic advantage of 80% of China’s oil imported by the sea travels along Indian Ocean routes through the vulnerable Malacca Straits[18]. What this allows is that this avenue covers the last reaming weakness or deficiency that Chinese policymakers have been concerned about for quite a long time. This can be compared to Chinese developments in Djibouti for establishing its overseas military facility and China believes as CPEC will assist China in isolating India from West CMEC can do the same from the East side[19].

Within the CMEC, New Yangon City Project, Kyaukpyu deep seaport and Thai Crown Polcphang group contributing further USD $ 1.4 billion projects in Yunnan Province, the infrastructural developments currently in China- Myanmar stands on a positive note[20]. These developments indicate a further expansion and development on the bilateral relations between both nations. The current concern that stands for both countries is the situation that is created by the military coup in Myanmar. The Chinese delegation is also trying to push towards a peaceful resolution in the nations and bring back NLD in power. Aung San Suu Kyi provides that endeavor that will allow China to further penetrate the land and progress with its development projects. The military rule will continue to provide hindrances to the Chinese progression and will further restrict further foreign direct investments that Myanmar has been receiving, for example, from Thailand.

In the post-coup period, how the Chinese have contributed to Myanmar’s fight against the Covid- 19 pandemic situation needs scrutiny. China is also building its ability to provide vaccines to its ally, and if it can receive Myanmar’s diplomatic and financial support again, then it can match New Delhi in terms of venture in vaccine diplomacy. Resuming these economic ventures is quite crucial as the progress of Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD) in terms of its multilateral development can match the economic ability that it hopes to develop via CPEC and CMEC[21]. BRI’s success heavily develops that Chinese ventures into the West and East are both equally matched and provide the estimated return of investments[22]. China-Myanmar relations provide the example of how bilateral relations can assist in nations maintaining their regional foothold and strengthen their sovereign powers. The ability to manifest infrastructural developments as strategic measures are the success that China and Myanmar need to maintain on a long-term basis.

Notes

[1] M.C. Miller (25th Feb 2021). “Myanmar- China ties: It’s complicated”. Hindustan Times, opinion.

[2] S. Karabel (12th March 2021). “Current developments in Myanmar in light of the dynamics of its relations with China”. Anadolu Agency.

[3] Rakhahari Chatterji, “China’s Relationship with ASEAN: An Explainer,” ORF Issue Brief No. 459, April 2021, Observer Research Foundation.

[4] M.C. Miller (25th Feb 2021), ibid.

[5] S. Karabel (12th March 2021), ibid.

[6] K. Yu. (15th April 2021). “How will Covid- 19 and the coup affect China’s belt and road investments in Myanmar and Southeast Asia?. South China Morning Post.

[7] Ibid.

[8] E. Campbell- Mohn (25th March 2021). “The Geopolitics and Protest: Myanmar, China and the U.S.”. LawFare.

[9] Ibid.

[10] L. Myers (26th May 2020). “The China- Myanmar Economic Corridor and China’s determination to see it Through”. Wilson Center, Asia Dispatches.

[11] A. Nachemson (17th March 2021). “China finds itself under fire in Myanmar”. ForeignPolicy

[12] Ibid.

[13] S. Tiezzi.(3rd February 2021). “What the Myanmar Coup Means for China”. The Diplomat

[14] J. Xianbai(19th January 2020). “China- Myanmar relations: An old friendship renewed by the Belt and Road”. CGTN.

[15] S. Ramachandra.(25th March 2021). “China and the Myanmar Junta: A Marriage of Convenice”. The Jamestown Foundation, China Brief, Vol. 21 (6).

[16] (17th April 2021). “Why is India not on the same page with its ‘Democratic Allies’ on Myanmar’s Military Regime?”. EurAsian Times, Indo- Pacific.

[17] R. Dayal (22nd March 2021). “China’s rail projects: A stratagem of statecraft”. Financial Express

[18] K. Yu. (15th April 2021). “How will Covid- 19 and the coup affect China’s belt and road investments in Myanmar and Southeast Asia?. South China Morning Post.

[19] T. Takahashi( 13th February 2021). “Its complicated: Myanmar and China have a difficult relationship”. Nikkei Asia

[20] Rakhahari Chatterji, “China’s Relationship with ASEAN: An Explainer,” ORF Issue Brief No. 459, April 2021, Observer Research Foundation.

[21] Y.N. Lee (4th April 2021). “China’s ‘laissez- faire’ approach towards Myanmar’s coup puts its own interests at risk”. CNBC

[22] Ibid.

Pic Courtesy- IDSA GIS lab

(The views expressed are those of the author and do not represent views of CESCUBE.)