Pakistan: The Struggling Story of Military Control

Despite the notion that Pakistan is a democratic republic with a parliament, the army has ruled for half of its 74-year history. Since 1947, Pakistan has been controlled by four different military rulers after three military coups. The National Assembly introduced the 18th constitutional Amendment in 2010 in an attempt to prevent the coup of a democratically elected government. As a result of the move, the president's unilateral right to dissolve the assembly has been removed. Although there has been a period of democratic power transition in Islamabad, the army's decision-making ability has not been curtailed.

The US boosted the Pakistan Army in response to the threat posed by the Soviet Union. As a result, the Pakistan Army were given advanced equipment. Because it considered it was a vital component in global politics, the army grew powerful, and the generals began to look down on lawmakers, wanting their own strategic space. Pakistan's world of politics has shrunk to the point where a military coup was unavoidable. In order to take power of additional assets, the army ignored the growth of the people. To justify continuing, it transformed Pakistan into a security-seeking state by over-emphasizing the threat from India, with a strong army regarded as a requirement for the country's survival. First Military meddling of Pakistan came in 1958 when President Iskander Mirza dissolved the constitution and established martial law in 1958, appointing Gen. Ayub Khan as the Chief Martial Law Administrator. A few days later, Ayub Khan was named President of Pakistan. Officially, the first martial law lasted 44 months, but Gen. Ayub Khan stepped down in 1969 and was succeeded by Gen. Agha Mohammad Yahya Khan. The second military coup occurred in 1977, when General Zia ul Haq and his troops abolished legislature and imprisoned Bhutto. When Zia ul Haq first came to power, he promised a more democratic referendum with a better outcome, but it soon became clear that Zia had no plans to leave. After carefully selecting Muhammad Khan Junejo as the nation's new prime minister, Gen. Zia ul Haq eventually resigned in 1985, ending Pakistan's second period of martial control. In 2007, Gen. Pervez Musharraf seized over after the Nawaz Sharif in the third and final military coup. Sharif had previously received criticism from the nation for withdrawing Pakistani forces from Kargil. Fearing a military coup, Sharif tried to remove Pervez from his office as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee, but this was not feasible because the army preferred Musharraf and rather than removed Sharif from his position and substituted him with Musharraf. With Asif Ali Zardari taking over as President, Musharraf ultimately resigned, putting an end to Pakistan's last military coup in 2008.

However, recently Imran Khan, Pakistan's prime minister, was deposed in a no-confidence vote in the house, puts an end to months of upheaval. Khan had been facing public outrage over his financial failure for weeks, and he had lost the confidence of Pakistan's formidable army establishment. The political opponents took advantage of the situation. Expert called it an end of the Hybrid democracy. Khan is the very first Pakistani prime minister to be deposed by a no-confidence vote, although no Pakistani prime minister has ever served out their entire five-year tenure. Pakistan has experienced two seamless power transfers via electoral politics: in 2013 and 2018. Pakistan, on the other hand, is not yet a functioning democracy; instead, it has functioned as a hybrid government, with the military pulling the strings through a flexible civilian bureaucracy. During Khan's four years in office, the military's domains of influence grew beyond security and foreign policy to include the economy, the media, and disaster relief.

Despite the army's declarations that it will restrict its function and desist from interfering in politics, history says contrary. Political upheaval in Pakistan has previously prompted direct military action. When it served its own purposes, the military has often skilfully retreated from politics, but it has not reluctant to participate in other situations. Khan's removal will be seen as a setback for the army's role in internal politics. In Pakistan, the military continues to play a powerbroker role. Khan's removal would have been impossible if the military had not discreetly withdrawn its support, which occurred amid acrimonious disagreements over the selection of Pakistan's intelligence head and the country's foreign policy. The military and its intelligence agency ceased pressuring partner political parties to support Khan's rule after losing out with the prime minister. Khan's removal from office follows a pattern: hand-picked prime ministers who take actions independently of the military's establishment ideology have been ousted from office. The political turmoil that preceded the no-confidence vote could have thrown Pakistan's democracy into disarray, but the country is not yet out of the woods. The pattern of chosen prime ministers refusing to complete their terms has yet to be broken. Despite the fact that legal safeguards resulted in the ouster of an elected leader, the true test of democratic power in the country will be whether the army remains out of politics.

Logically, one may not expect a military that has had access to excess power and management of the entire country since its foundation to instantly succumb for a regime that is so idealistic to them as 'Democracy.' However, the main issue is that military officials believe that elected elites have failed to offer effective governance in the past, so they assume they can achieve what politics have unable to do. After been introduced to ultimate political powers, such as those exercised during martial rule or extraordinary decrees, the military is hesitant to relinquish all such powers. It's important to admit that the Pakistani army can't and won't ever perform a role in safeguarding a peaceful, democratic country. However, it is extremely doubtful that the military's dominance would be diminished in the nearish term; rather, the military will discover new ways to grow its capabilities and control over Pakistani politics, as it is doing now.

Notes

1. ‘Pakistan’s rise to Military Rule and its Political and Societal degeneration’ – Center For Land Warfare Studies (CLAWS): https://www.claws.in/pakistans-rise-to-military-rule-and-its-political-and-societal-degeneration/

2. Explained: How army is still deciding course of Pakistan politics - Times of India: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/world/pakistan/explained-how-army-is-still-deciding-course-of-pakistan-politics/articleshow/90626474.cms

3. Why is the army in Pakistan dangerous for democracy? Answer goes back to 1947: https://theprint.in/opinion/why-is-the-army-in-pakistan-dangerous-for-democracy-answer-goes-back-to-1947/524467/

4. Washingtonpost.com: Army Seizes Control in Pakistan: https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/inatl/longterm/southasia/stories/pakistan101399.htm

5. 1958, 1977 & 1999: How the Pakistan Army Overthrew Civilian Govts Over the Years: https://www.thequint.com/news/world/pakistan-prime-minister-president-government-military-takeovers-coups

6. Pakistan military still controls Kashmir policy: https://www.aninews.in/news/world/asia/pakistan-military-still-controls-kashmir-policy20220425110027/

7. With Imran Khan's Ouster, Pakistan's Military Ends Its Experiment With Hybrid Democracy: https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/04/25/pakistan-military-imran-khan-hybrid-democracy/

8. How Imran Khan’s removal affected civil-military ties in Pakistan | Military News | Al Jazeera: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/4/19/how-imran-khan-removal-civil-military-ties-pakistan

9. Imran Khan’s failure exposes Pakistan’s military problem | Pursuit by The University of Melbourne: https://pursuit.unimelb.edu.au/articles/imran-khan-s-failure-exposes-pakistan-s-military-problem

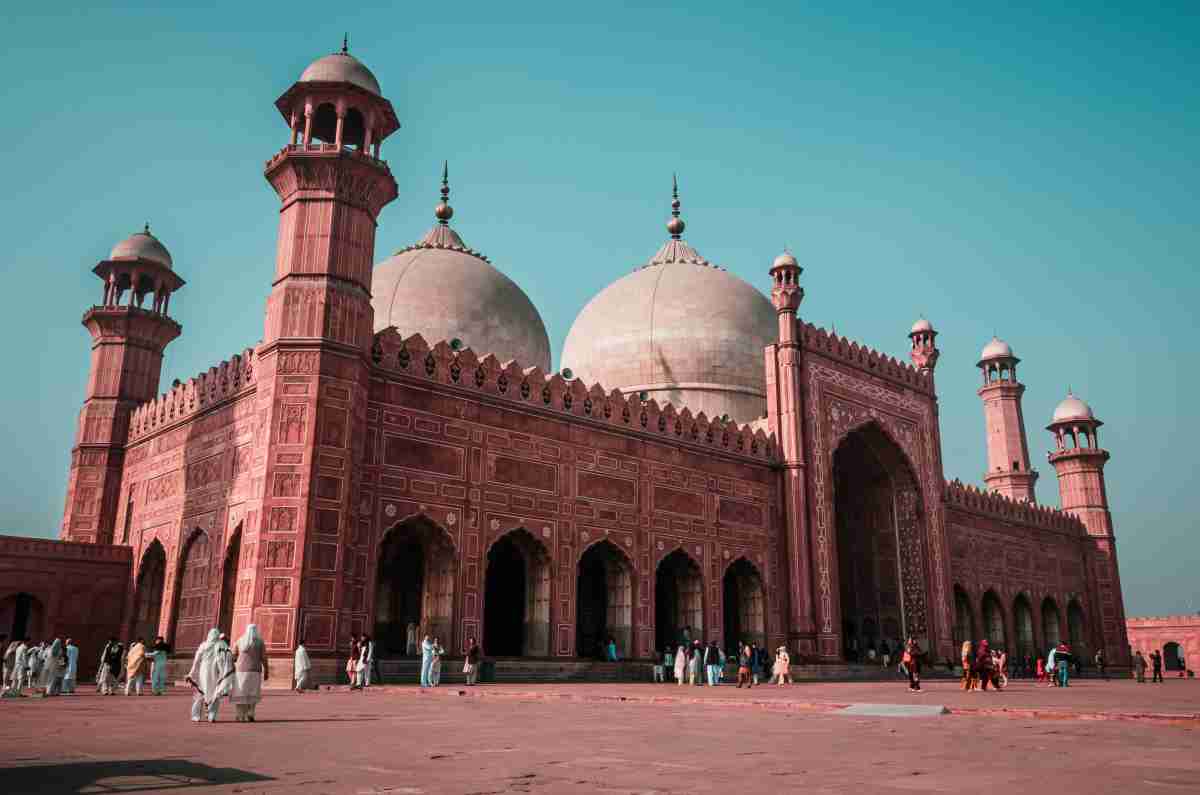

Pic Courtesy-Mohammed Amer at unsplash.com

(The views expressed are those of the author and do not represent views of CESCUBE.)