Minilateralism in the Indo-Pacific: The India-France-Australia Triad

Rory Medcalf, in his essay “What’s in a name” noted that “Indo-Pacific minilateralism is the wave of the future that many countries will try to surf.”[1] The recent tide of trilateral and quadrilateral groups hints at the significance of this arrangement in international politics.

In the backdrop of the UN celebrating its 75th anniversary last year, many scholars and experts have questioned the present state of multilateralism that has been pushed to the brink by the pandemic. At the same time, there is a consensus on a greater need of multilateral order to foster cooperation and deal with the crisis. Minilateralism is best described by Moises Naim in his essay On Minilateralism (2009) as “the smallest number of countries needed to have the largest possible impact on solving a particular problem.”[2]

The first meeting between the trilateral group was held in September 2020 at the Foreign Secretary level. The Indian delegation was led by Harsh Vardhan Shringla. The MEA statement reiterated upon the “focus of the dialogue was on enhancing cooperation in the Indo-Pacific Region.”[3] A follow up meeting was held on February 24th of this year, at the senior officials’ level where Shri Sandeep Chakravorty, Joint Secretary (Europe West) led the Indian side. While the first meeting stressed upon issues of multilateral institutions, maritime global commons and a rules-based order in the Indo-Pacific, the second meeting outlined explicit issues including “Maritime Security, Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR), Blue Economy, Protection of Marine Global Commons, Combating Illegal, Unregulated and Unreported (IUU) Fishing and Cooperation in Multilateral Fora.”[4]

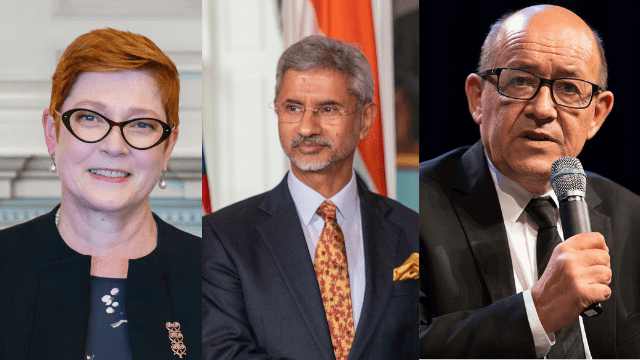

India-France-Australia

The idea for the trilateral was mooted by the French Prime Minister Emmanuel Macron back in 2018 in Sydney, when he talked about the need for “a Paris-Delhi-Canberra axis as a key for the region with joint objectives in the Indian-Pacific region.”[5] The rationale behind establishing such a forum stretches from strong bilateral ties and presence in Indo-Pacific to security interests of each state.

With a population of 1.45 billion (18.7%) of the world’s share, the three countries are part of the top 15 economies in the world and members of G20. India and France share historic ties and have been strategic partners since 1998. India and Australia elevated their relationship to Comprehensive Strategic Partnership (CSP) last year in Prime Minister Modi’s first ever virtual summit. While France is an integral partner in the defence sector for India, Australia remains the top supplier of coal, particularly coking coal to India. France and Australia also share a strong relationship with diplomatic engagement since 1842. The three democracies share similar visions for an inclusive and rules-based international order. In the Indo-Pacific context, India is central to the geographic construct, Australia acts as a bridge in connecting Indian and Pacific oceans, and France is the only resident European power with a presence of 1.5 million population on its island territories in the region. India and Australia are also a part of the most important minilateral — the QUAD, with France seen as a “natural” fit to the group. In the first week of April, France conducted a naval exercise La Perouse 2021 with QUAD members in the Bay Bengal. The exercise was designed to conduct training, enhance cooperation in maritime surveillance, maritime interdiction operations, and air operations.[6] It is a stellar example of presence of a naval theatre in the region.

The Geopolitical Context

The realities of a changing geopolitical context shaped the trilateral and continues to drive the focus of the group. China’s assertiveness and wolf warrior diplomacy has affected both small and big regional powers. It opened a standoff with India at the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in the Ladakh region while bullying Australia in handling its exports. Thus, countering China serves as one of the greatest convergence of interests for the three countries. While none of the individual statements or the joint statement of the trilateral dialogue mention China by name, its actions are hinted at through direct and indirect means. The French statement came the closest in calling out China as its statement highlighted “the goal of guaranteeing peace, security and adherence to international law in the Indo-Pacific.”[7]

The Indo-Pacific continues to be the geopolitical hotbed and will likely shape this century’s regional and global power politics. Commenting on the rationale of the group, Rajeswari Pillai, Director of the Centre for Security, Strategy & Technology (CSST) at the Observer Research Foundation, noted a crucial “capacity issue” where individual capacity of navies is inadequate to protect the region’s security interests.[8] Amidst presence of a stronger Chinese naval power, China, coming together against a common threat is the need of the hour.

Rise of Minilaterals

The phenomenon of minilaterals is not new to international politics. The G20 was formed back in 2009 as a response to the 2008 financial crisis.[9] The coalition of Brazil-Russia-India-China-South Africa or BRICS is another such example of like-minded economies. In the Indo-Pacific region, the India-Japan-Australia trilateral has existed since as far as 2015, a Japan-America-India (JAI) dialogue took place in 2018 and Australia-India-Indonesia has its meetings in Canberra and Delhi. On the rising minilaterals in the region, several experts voiced their concern over exclusion of ASEAN states in the minilateral building exercise of Indo-Pacific, moving away from the context of ASEAN centrality. The most important minilateral of the region — QUAD, comprises all non-ASEAN states even though there are talks to involve Indonesia, Vietnam and New Zealand in a QUAD Plus arrangement.

The shift towards smaller groupings was visible for some time, but the pandemic has accelerated the process. Such groupings are now more visible and have emerged from the sideline to the centre point of global governance. With the extent of geographical expanse, the size of population (around 60% of the world) and a concoction of all developed, developing and LDC economies, the need for voluntary, informal and issue-based groups became a necessity. How the yardstick to measure the success of a minilateral grouping is vague and not universal. There are multiple factors involved in the creation and functioning of a minilateral like the issue, level of bureaucracy and formality, structure, number of meetings, legitimacy, etc, that vary with each type of group.

With new and emerging threats such as climate change, non-traditional security, pandemics, a renewed multilateralism is required to find practical and long-term solutions. The “magic number” — the right number of countries in a group — as proposed by Naim is crucial to break the gridlock of large multilateral institutions that last came to a consensus in 1994 for formation of WTO.[10] However, minilaterals can complement a multilateral system but cannot replace its complexities and relevance in diplomacy and global governance. A rules-based order can be effectively maintained only through coming together of all stakeholders on the same platform rather than multiple and competing platforms for the same task.

References:

[1] Rory Medcalf. “What’s in a Name.” The American Interest (2013)

[2] Moises Naim. “On Minilateralism.” Foreign Policy (2009)

[8] Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan. “Rise of the Minilaterals.” The Diplomat (2020)

[9] Aarshi Tirkey. “Addressing the inefficacy of multilateralism — Are regional minilaterals the answer?.” ORF (2020)

[10]Moises Naim. “On Minilateralism.” Foreign Policy (2009)

[11]Dr. Pragya Pandey. “India-France-Australia: Emerging Trilateral in the Indo-Pacific.” Indian Council of World Affairs (2020)

Pic Courtsey-headline8.in

(the views expressed are personal views of author and do note represent views of CESCUBE.)